C. Kevin Boyce is Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Stanford University. Speaking to Srijana Mitra Das at Times Evoke, he discusses how plants have formed the world we know

On the core of his research –

Professor Boyce is interested in the evolution of life on land that occurred over the last 400 to 500 million years. The real foundation of that is known from the plant and fungal fossil records — these provide insights into the biology and physiology of organisms. That relates then to other disciplines like studying how the biota affects climate, the carbon cycle, plant productivity, etc., seen over time.

On the findings on the evolution of leaf vein density and why this event is so important –

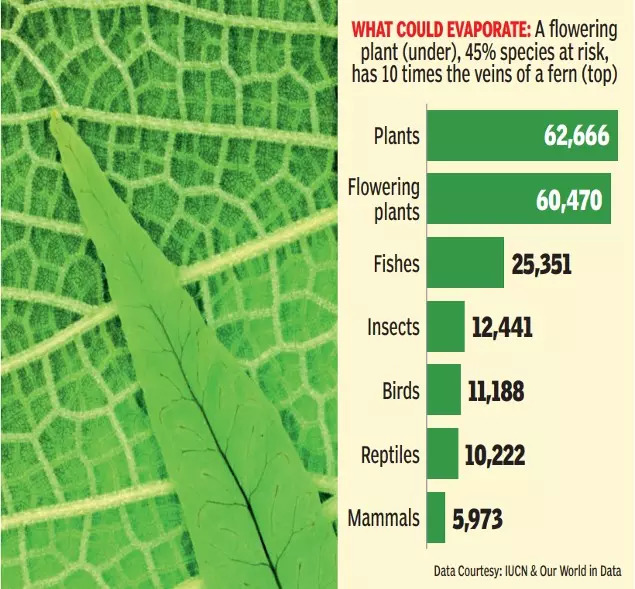

Leaf veins move water — this transfer is essential to what plants try to accomplish because in order to do photosynthesis, carbon dioxide (CO2) is brought in past the pores in a leaf to then be fixed as a sugar. The more CO2 that is take in means, the more photosynthesis, can be done. The density of veins (image above) is very tightly correlated with how much water a leaf can afford to lose. But as water moves through a leaf, it has to pass through leaf pipes and tissues which are not designed for such transport — anything that shortens that distance lowers the resistance overall. The more veins you have, the shorter that distance becomes. So, the plant can move more water — and do more photosynthesis.

On how this can put rain in the rainforests –

We can look at this whole process through time and track how it changed — through the last 400 million years, the density of veins was very stable. But this increased dramatically in the flowering plant lineage that evolved about 120 million years ago — so, in the modern world, which is dominated by flowering plants, much more water is lost by these. This is called transpiration or the process by which water is brought up from the ground and released into the atmosphere. Now, in a tropical rainforest, about half the rain which falls there actually comes from the rainforest itself. It is recycled by plants as it falls out of the sky — they put it right back up there.

On ‘the long-term carbon cycle‘ –

We all learn about the carbon cycle in school when we study soils, the oceans, tractors, factories, etc. — this is the short-term carbon cycle. Here many changes go on very rapidly. It’s not that much when we think, for instance, of how much carbon is stored in limestone rocks or coal and such large geological reservoirs. But if one thinks about longer geological time, over millions of years, there are very different exchanges with how much CO2 has come out of volcanoes, how much coal has been deposited, etc. These matter over the longer term — and plant fossils show us these changes as well. System Dynamics modeling and Simulation can be done for analyzing the Carbon cycles – our comment

On flowering plant fossils offering insights about climate change?

They do. The density of pores found on leaves is tied to how much CO2 there is in the atmosphere — if there is less CO2, you have more pores on leaves to compensate. These are key ways we know about such dynamics. fossils also reflect broader mechanistic ways plants influenced climate.

On, how did the evolution of Palaeozoic land plants create ‘meandering rivers’ –

The existence of complex large plants on land shapes how water moves across a surface — as larger plants evolved, they stabilized riverbanks and impacted how sediment flowed across a landscape. If one goes back to a world before such plants, sediments would have been washed out into the oceans. Rivers stabilized with plants as levees built up on their sides. During floods, those got breached — sediments thus went laterally into the plains on the sides of the rivers and were held on land.

On What is the most fascinating plant fossil he has studied so far?

His personal favourite is the real oddball fossil, something you look at and there is nothing like it, so you have to go back to first principles and think, what could this organism be doing? How did it interact with its environment? Was it receiving more or less light? Was it capable of greater gas exchange? Could it be photosynthetic? There is also what is possibly a giant fungal fossil (image, lower L) called Prototaxites — this was around 20 feet in height while the highest contemporary trees over 400 million years ago were just a couple of feet tall. Even within the domain of plants which have modern descendants, there are giant tree fossils like copses that are millions of years old. The wonder is – how could they do photosynthesis, grow, and hold themselves up.

On why is Palaeobotany needed to understand our current world –

The world has been much warmer and much colder earlier than now. Understanding such fluxes and that range is important. Any study of modern ecology must differentiate between what might be noise or perturbation in the system versus possible longer-term characteristics — we need that context of history to understand the world we live in now. Our comment – This is necessary considering some narratives that are being discussed, without taking a holistic perspective.

Discover more from rasayANix

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.