Historian Corey Ross is Director of the University of Basel’s Institute for European Global Studies. According to him the European Colonial powers used the power of water to expand and create new hierarchies of access. In this summary of the conversation with Srijana Mitra Das at Times Evoke, the colonial history of water; and, why this matters now is explained by him:

On what is the core of his research –

He works on environmental history, and studies the interrelationships that formed between human societies and the rest of nature. he does this particularly in the context of Europe’s overseas colonization. In his book ‘Liquid Empire: Water and Power in the Colonial World’, he focusses on water to examine imperial power, resistance and interconnections between how humans constructed societies and hierarchies.

On the role played by water in imperial expansion worldwide –

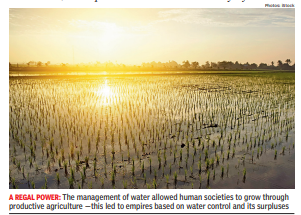

Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia were built on the control of water — ruling over water made land and labour more productive, which brought greater military and economic power to rulers. It also allowed them to demonstrate beneficence to subjects, contributing thus to political and social stability. When European colonisers took over some cradles of hydraulic civilisation in parts of India, Java or the Middle East, they were drawn to water control for the same reasons. Water is a reflection of power relations and a producer of these those who hold sway over it also control several other aspects of life.

On What technologies did the colonial control of water involve –

This took different strategies, including using new technologies to supposedly improve older irrigation systems, build entirely new ones to open dry lands to cultivation, use industrial techniques like dredges and steam power to drain swamps and clear marshlands for agriculture, utilise hydro power and attempt to modernize fisheries. It also involved the creation of new navigation routes and networks, even changing coastlines and rivers to make them conduits of commerce and projections of political and military might. There were trade-offs between using a river for irrigation or navigation, the two having very different requirements. Equally, irrigating areas upstream or draining marshes near coasts might aid farming but had adverse impact on fisheries.

On could colonial administrations entirely control water –

Despite all the claims by European colonialists of having mastered nature — which was an important way to justify their rule water was never mastered. All these attempts at control often caused negative consequences like malaria epidemics breaking out near irrigation canals or water logging and salinization of land, which remain a huge problem. A failure to harness water effectively also translated to a responsibility for problems — water became a flashpoint of many anti-colonial protests, such as when colonizers tried to close wells for sanitary reasons and start charging for a resource which used to be free.

On role played by water in the huge commercial expansions of colonialism –

In Mumbai, the first large hydroelectric plants were built in the early decades of the 20th century, specifically to support the city’s textile mills. Hydroelectricity emerged as a relatively cheap and cleaner source of energy. This led to protests upstream though against the flooding of vast areas in the Western Ghats. The then-princely state of Mysore used state investment to boost mining at the Kolar Gold Fields and grow manufacturing by developing electric plants at the Kaveri Falls’ Shivasamudram. This was observed in the context of Africa too. This led to the phenomenon in both the African and Asian contexts of hydroelectricity being developed for distant urban markets, bypassing potential rural markets which were considered unviable. This was based mostly on prejudices about the extent to which ‘ordinary’ people in the colonies were ‘ready for’ something as exotic and new as electricity — thus, most rural electrification happened only after freedom. With most people engaged in agriculture, the only way to do this development was by improving farming productivity — irrigation played a key role, creating agricultural surpluses which could then be invested into industry.

On the implications of the colonial approach to water in a postcolonial world which is also facing an environmental crisis –

Most of the severest water related problems are in the Global South and in former colonial territories. One challenge is that governments, international NGOs, donor countries, development banks, etc., tend to opt for technological solutions to water problems. We must trace those continuities of how people try to deal with water by using ‘technological solutions’ rather than addressing traditional knowledge systems, examining local usages of water, etc. The IPCC highlights highly water-vulnerable regions like South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and parts of South America their problems are not a matter of natural difference. A recent IPCC Assessment Report (2023) specifically cites colonialism not just as a driver of climate change but also a critical factor in explaining the differential vulnerabilities of groups to this. Water, through its profusion or lack, is the main medium through which all the impacts of climate change are manifested — recognising its colonial legacies is extremely important in the effort to find solutions to changes in the water cycle caused by global warming now.

Discover more from rasayANix

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.